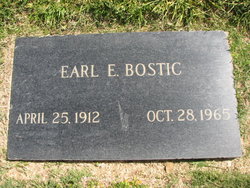

EARL BOSTIC

by Fred Patterson

Earl Bostic was a saxophone player who is often maligned, misjudged and/or misrepresented. He has been referred to as a pop instrumentalist, a screaming R&B saxophonist and a jazz musician. He was all of those, plus an outstanding technical player and improviser. On recordings, his is one of the most identifiable alto saxophone sounds there ever was--right up there with Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker. Jazz legend John Coltrane learned about technique when he played in Bostic’s band during the early fifties. This has been documented. Yet Bostic has never been recognized as the major jazz player that he was.

Eugene Earl Bostic was born on April 25, 1913 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He earned a degree in music theory at Xavier University in New Orleans and spent his formative years playing in territory bands that performed in South Western and Midwestern cities and towns during the early thirties. In 1938, he moved to New York City and began to make a name for himself playing in the orchestras of Cab Calloway and Don Redman and leading combos in the many nightclubs.

On October 12, 1939 at a recording studio in Manhattan, Earl Bostic recorded with a group of musicians that included Henry “Red” Allen on trumpet, J.C. Higginbotham on trombone, Clyde Hart on piano and Big Sid Catlett on drums. The session was led by vibraphonist Lionel Hampton and also included the great guitarist Charlie Christian. Bostic played with the best, even at this early stage in his career.

Also that year, Bostic began an engagement at Small’s Paradise in Harlem that lasted four years.

Bostic worked as an arranger and wrote the song “Let Me Off Uptown” for the Gene Krupa Orchestra and it became a hit featuring trumpet player Roy Eldridge and singer Anita O’Day in 1941. Louis Prima cut Bostic’s “Brooklyn Bridge” and Alvino Rey had a hit with his “The Major and the Minor.”

During this period, Bostic took part in the after-hours jam sessions at Monroe¹s Uptown House and Minton’s Playhouse, places that were frequented by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and other proponents of the new be-bop music. Bostic took part in so-called cutting sessions with Bird and held his own, according to witnesses (see Swing to Bop by Ira Gitler).

Around 1943, Bostic joined Hampton’s big band and toured with it during the first recording ban of the forties. When the ban was lifted in 1944, Bostic recorded two dates in March--one produced “Flying Home No. 2” featuring Arnett Cobb and Cat Anderson, the other was a V-Disc recording--then left to join the group of Hot Lips Page. On September 12, 1944, Bostic was the alto player at a Page session in New York City that featured the tenor saxophonists Ben Webster, Don Byas and Ike Quebec. Among these giants, Bostic solos on the jump numbers “Good for Stompin” and “Blooey.”

Bostic led his own session for the first time in November 1945. He cut four tracks that were issued on the Majestic label. Musicians included Benny Harris (trumpet), Benny Morton (trombone), Don Byas (tenor saxophone), Tiny Grimes (guitar) and Cozy Cole (drums). The session produced some fine, swinging numbers, but none were hits. Concurrently, Bostic recorded with Hot Lips Page’s orchestra through 1946.

That year, Bostic signed to the Gotham label. For two years, Bostic cut a series of records containing a bluesey, swingin’ style that was popular during this era--a transition period between big band swing and the jump blues that would soon morph into rock and roll.

Bostic’s style was in full effect during these early sessions, especially on his jumped-up version of the Erskine Hawkins hit “Tippin’ In,” recorded at the first Gotham session in March 1946. Also recorded then, but not released until about a year or so later, was an old Tin Pan Alley song called “Liza.” Bostic would reach into his bag of old standards from time to time and this would serve him well, commercially.

In July, Bostic cut “Jumpin’ Jack,” a song that featured him singing, not unlike a Louis Jordan record. In fact, many of his Gotham recordings are similar to Jordan¹s recordings of the time--including “That’s the Groovy Thing,” “Let’s Ball Tonight” and “Cuttin’ Out.” Bostic’s trumpet player Roger Jones often sang the ballads. In 1947, Bostic and his group appeared in an all-black movie called I Ain¹t Gonna Open That Door. For this occasion, the ex-Duke Ellington singer Joya Sherrill worked with him.

1948 was a significant year for Bostic. He recorded a song called “840 Stomp” that showcased his stratospheric playing, reaching notes so high you’d swear he was playing a clarinet. Also, he and his band recorded another older song, “Temptation.” It had been a hit for Bing Crosby in 1934. The song became a bona fide hit for Earl Bostic when it reached the Top Ten of the R&B chart during the summer of 1948.

At this point, the much larger King Records stepped in and purchased Bostic’s contract and all his recorded masters from Gotham and began to reissue them. At King Records, Bostic became a prolific recording artist whose records sold to R&B, jazz, pop and adult markets. With the rising popularity of the long player, Bostic’s albums likewise did well.

Bostic must have loved the sound of Lionel Hamptons vibes, because in 1950 vibist Gene Redd joined the band and from this point on, nearly every one of Bostic’s records included a vibe player--usually Redd, who remained in the group until 1958 when he became a producer and A&R man for King Records. Even after that, Redd often sat in during recording sessions.

King was rewarded for its devotion to Bostic and his music in 1951, when “Sleep” (a song from the twenties) went to Number Six and “Flamingo” (which dates to Duke Ellington’s hit version of 1941, but may be older) topped the R&B chart.

Around the spring of 1952, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane joined Bostic’s touring and recording group. Coltrane has been quoted as having said that Bostic had “fabulous technical facilities” and that “he showed me a lot of things on my horn.” (See A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album by Ashely Kahn.)

Other members of Bostic’s group that went on to make names for themselves include Blue Mitchell, Tommy and Stanley Turrentine, Benny Golson and Teddy Charles. During the fifties, when Bostic recorded in Los Angeles, he made use of such fine session musicians as Earl Palmer, Benny Carter, Barney Kessel, Teddy Edwards, Rene Hall, Roy Porter and Ernie Freeman. Bostic was clearly working with some excellent musicians.

King records released more than 80 45s, 63 EPs, 11 10-inch LPs and about 25 full-length albums--nine of them released in 1959 alone! Most of the albums consist of rocked-up versions of old standards—i.e. “Night and Day” done to a slight rock beat—but Bostic’s inimitable sound gives them new life. He takes the melody to places it has never gone before, and may never go again.

In 1963, Bostic cut two straight jazz albums at the World Pacific Studios in Hollywood, California: Jazz as I Feel It and A New Sound. He received support from organ player Richard “Groove” Holmes, guitarist Joe Pass, drummers Earl Palmer and Shelly Manne, and bass player Al McKibbon. These are excellent examples of organ-sax combos and show a side of Bostic that is rarely heard, especially on a few of the songs that stretch longer than the three-minute single.

In the late fifties, Bostic had a stroke and he had to slow down his pace. Bostic died of a heart attack while on tour in Rochester, New York on

October 28, 1965. About a year or so later, The Song Is NOT Ended, an album of ballads, was issued on the Philips label.

Fred "Phast Phreddie" Patterson is Head Archivist of the ARChive of Contemporary Music in New York City and has researched Earl Bostic (and many more) extensively.